|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

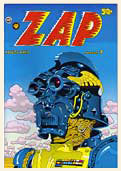

Zap Comix #1 |

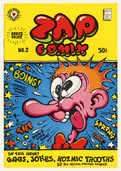

Zap Comix #2 |

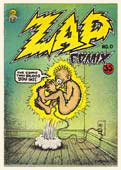

Zap Comix #0 |

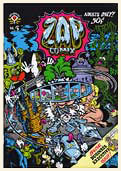

Zap Comix #3 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 9 |

REVIEW SCORE: 9 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zap Comix #4 |

Zap Comix #5 |

Zap Comix #6 |

Zap Comix #7 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 9 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 9 |

|

|

Zap Comix

1968-2005 / Apex Novelties - The Print Mint - Last Gasp

1968-2005 / Apex Novelties - The Print Mint - Last Gasp

|

There were many precursors to the underground comix revolution in 1968, including college humor magazines that featured cartoons and strips from Joel Beck, Jack Jackson, Vaughn Bodé, and Gilbert Shelton, and Surfer magazine that featured cartoons from Rick Griffin. There were fanzines and low-distribution periodicals that featured strips from Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson, and Cavalier and Harvey Kurtzman's Help! magazine also published early cartoons by several of the people named above. Books and small art magazines came out with unconventional art and comics from people like Joe Brainard and Robert Ronnie Branaman. Frank Stack, George Metzger, Spain Rodriguez, Kim Deitch and Art Spiegelman, among many others, were all getting into countercultural art and comics in some way.

There were many underground newspapers, like L.A. Free Press and East Village Other (EVO), that published comics from almost all of the forefathers of underground comix. Dan O'Neill's Odd Bodkins comic strip was syndicated in dozens of mainstream newspapers in the mid '60s. Charles Plymell printed a portfolio of artwork by S. Clay Wilson in Lawrence, Kansas, before they both ended up in San Francisco. Several comic books (many of them magazine-size) were produced by either amateur publishers or institutions, including Bodé's Das Kampf, Jackson's God Nose, Stack's The Adventures of Jesus, Beck's Lenny of Laredo and The Profit, and Shelton's Wonder Wart-Hog Quarterly.

But none of these had a fraction of the impact that Robert Crumb's Zap Comix #1 had when it came out in San Francisco on February 25, 1968. Crumb had been busy himself for over a decade, producing his own fanzine and private comics, working odd commercial illustration jobs, and later publishing comics in EVO and Philadelphia's Yarrowstalks (another underground paper). Brian Zahn, publisher and editor of Yarrowstalks, put out an all-Crumb issue in 1967 and suggested that Crumb draw some actual comic books that Zahn would publish. Crumb was thrilled and produced two 24-page comic books with the title Zap Comix in the fall of 1967.

Crumb sent the original artwork for one of the comic books to Zahn in Philadelphia and sent a set of photocopies of the same artwork to William Cole in New York. Cole was assembling a compilation of Crumb's comics for Viking Press that would become Head Comix. Crumb didn't hear from Zahn for months, so he finally called Zahn's office and was told, "Oh, he went to India, man." The original art for Zap Comix #0 disappeared with Zahn for several years, but that didn't slow down Crumb. He still had the original art to the other issue of Zap when he was introduced by mutual friends to Don Donahue in early 1968.

When Donahue saw the pages of artwork for Zap Comix #1, he quickly agreed to publish the book. Donahue approached Charles Plymell, a beatnik poet who had his own small print shop, and agreed to trade him a tape recorder in exchange for 5,000 copies of Crumb's comic book. They set to work printing the book on an antiquated, pre-war Multilith 1250 printing press, which had to be constantly monitored to keep the color covers in registration and from jamming on the surplus paper.

While Plymell and Donahue were printing Zap #1, S. Clay Wilson strolled into the print shop after moving from Lawrence, Kansas. Donahue introduced Wilson to Crumb, who was amazed by the full-page drawings Wilson had done for Grist Magazine, a poetry anthology published by John Fowler in Lawrence. Zap Comix suddenly had a second artist to feature. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

|

Zap Comix #1 ventured into the city of San Francisco in a most curious manner. Donahue, Crumb's first wife, Dana, and her friend Mimi tossed a few stacks of the book into a baby stroller and went out to sell them on Haight Street. Though well received by some, the book wasn't quite an instant hit, and some of the hippie shops that Donahue expected to be enthusiastic retailers rejected it. What you sellin'? Hippie comic books? What a stupid idea.

|

|

|

Photos and ledger from Zap Comix #1

(click for larger image)

|

|

But it didn't take long for Zap Comix #1 to sell reasonably well, and within weeks a second printing was produced and work was well underway for the second issue. Crumb had already invited Wilson to contribute, but he wanted more artists to join him. He'd seen Rick Griffin's The Family Dog rock poster while he was working on Zap Comix #1 and it was unlike anything he'd seen before, with its "Sunday Funnies" layout, panels of surreal cartoons and talk balloons with mostly nonsensical, abstract lettering. Crumb said the poster inspired him to look at comics in a new way, leading him to create "Abstract Expressionist Ultra Super Modernistic Comics" for Zap #1, which featured surreal cartoons in oddly jagged panels with abstract lettering.

In the spring of '68, Crumb showed up on Griffin's front porch and asked him to contribute to Zap Comix. Griffin suggested his friend Victor Moscoso would be another rock poster artist who'd be interested in the comics medium. Griffin showed Moscoso Zap #1 and Moscoso was floored. "I saw potential in it that I wasn't seeing up to that point," Moscoso said. "I was ready for it." Moscoso led the way to forming a legal partnership with Crumb, Wilson and Griffin and registering Zap as a trademark. From that point forward, all decisions about the comic book were made as a collective, with each member wielding veto power on future contributors.

In July of '68, Zap Comix #2 was ready to print, and the collective agreed to shift from Plymell's rickety old press (now owned by Donahue) to The Print Mint, a major rock poster printer with better quality control and higher-volume printing presses (and a printing vendor who could handle any extra work that was needed). The Print Mint had already launched Yellow Dog in May of '68, though it was a tabloid comic at first and not a comic book. Donahue was disappointed when Zap moved on, but his Apex Novelties remained as the "official" publisher of record until the seventh issue, and anyway he would soon be printing a gazillion Snatch Comics and other smut digests.

The second issue of Zap included contributions from all four members of the group, and they inspired one another to really push the comic art envelope. Around the same time, Crumb had tracked down the set of photocopies of the original Zap Comix artwork he had mailed to William Cole in New York. He got those back, touched up the photocopies, and The Print Mint published the third issue of Zap not long after #2. But because the third issue was actually the first incarnation of the comic book, they titled it Zap Comix #0 to preserve a true chronological numbering system.

By the fall of 1968, underground comix had evolved into the newest hip thing in the counterculture, led by the three issues of Zap. Other artists began to jump in on the concept and a few more titles were launched, including Feds 'n' Heads and Bijou Funnies. The fourth issue of Zap (#3) was published by the end of the year, and with Gilbert Shelton's contribution to the book, he was invited to join the Zap Collective. The fifth issue (#4) would follow in 1969, introducing Spain Rodriguez and Robert Williams to the series. That same year, Rodgriguez and Williams were the last two members invited into the Collective. The seven artists in the fourth issue would contribute to almost every issue of Zap in the next 35 years, except for Rick Griffin, who died in 1991.

The creators of Zap never rested on their laurels and kept doing things that had never been done in comic books before. They saved some of their most egregious sexual cartoons for Snatch and Jiz, but they weren't afraid to let it all hang out in Zap as well.

|

When Zap Comix #4 came out in the summer of 1969 it caused a huge stir, primarily because of Crumb's "Joe Blow" story, which depicted a family enjoying incestuous relations. The rest of the issue was almost as daring. Retailers (who were now on board with Zap in a big way) were arrested on both coasts for selling Zap #4. The Print Mint was raided by local police, causing proprietors Bob Rita and Don Schenker to hide all copies of the book from the cops and mount an expensive legal defense, limiting their ability to prosper.

|

|

|

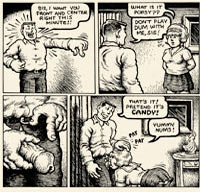

Detail from "Joe Blow" in Zap Comix #4

(click for larger image)

|

Although two booksellers in New York were convicted of selling obscene material, none of the legal charges against The Print Mint held up, and a year later things were relatively back to normal. Zap #5 came out in 1970, by which time underground comic books were exploding with popularity all over the country. New publishers, titles and artists were launching careers in the genre and the counterculture market was gobbling up the product. Mainstream media recognized the new craze and started cashing in. This is when the phrase "Keep On Truckin'" (from Zap #1) began to appear on anything and everything marketed to the hippie culture, mostly without Crumb's permission or participation.

But by this time, Crumb was a countercultural superstar. He was finally making decent money in his career as a comic artist, yet he had also turned down most of the most lucrative commercial offers from various entities, including advertising for automobiles, Playboy and the Rolling Stones. He despised modern pop culture and had equal disdain for hippies, yet he was constantly fucking the best looking hippie girls around (which didn't help his marriage with Dana). This cynical and conflicted period of his life (which would last for years, if not a lifetime) was reflected in his comics for Zap and other comic books.

For two-and-half years, The Print Mint kept reprinting the first six issues of Zap and selling them like hotcakes, passing the one million mark of copies sold in 1972. Finally, Zap Comix #6 came out in 1973 and sold very well, despite the waning of the golden era of underground comix. The next two issues were published in two consecutive years before the Collective took a three-year break in the mid '70s. This was around the time that Crumb was kind of burnt out on comics and getting into music with his band, R. Crumb and his Cheap Suit Serenaders, which produced three albums in the '70s. And as Crumb would admit himself, he was also worn out by the internal politics associated with the highly profitable Zap Comix series. He wanted to open the book up to other comic-book creators, but he found little support from other members in the Collective, who didn't want to divvy up the profits or the page count to new members. Gilbert Shelton was also in favor of a more open-door policy, but neither Crumb nor Shelton could convince the others to relent, and each and every member had that veto power that Moscoso had set up from the second issue.

But by 1978, the Zap Collective roped Crumb into another book and Zap Comix #9 was published. It was one of the last comics published by The Print Mint, which would soon get out of the publishing business altogether, and the title would be taken over by Last Gasp. But after #9, future issues of Zap would only come out every three or four years, getting longer and longer between issues. Rick Griffin died in 1991 and Paul Mavrides was selected to replace him as a regular contributor. The final issue, #15, was published in 2005. Since then, Spain Rodriguez has passed away and S. Clay Wilson is in very poor health. In 2014, Fantagraphics announced the pending arrival of The Complete Zap Comix, a five-volume, slipcased hardcover set that will also include the 17th unpublished issue with work by the Zap Collective (including Rodriguez and Wilson). The collection is over 900 pages and costs $450 on pre-order.

Zap Comix ended up selling millions of copies, second only to the Freak Brothers in underground comics popularity and easily the most influential comic book of its era, and perhaps any era. Its impact is sorely overlooked in current popular culture, but it opened doors for the entire spectrum of alternative comics, small press comics and graphic novels that exist today. It led to the entire comic-book industry changing its business culture, respecting its creators, and expanding its marketplace to include adult-oriented comic publications. And even for mainstream comic-book fans, Zap helped lift the most popular superheroes to new heights of maturity and complexity.

More than that, Zap Comix blazed new trails in straightforward content, storytelling and graphic communications. Even before Justin Green's groundbreaking Binky Brown, Robert Crumb was pitching confessional comics into our unprepared minds. Victor Moscoso and Robert Williams were transcending traditional story structure and transforming comics back into a visual art form rather than a narrative one. S. Clay Wilson was combining the visual and the narrative into a single, complex panel that blistered our eyes while enlightening and/or sickening our psyches. Rick Griffin was unleashing majestic, visionary panoramas that reached for our soul. Each of these creators influenced entire branches of comic-book artists and writers who, in turn, influenced new generations of creators.

And most impressively, Zap Comix became a standard bearer for high-quality and innovative comic creation. The contributors to Zap knew they could never just throw together haphazard comics to make a quick buck, nor would they want to. From issue #0 to issue #15, the men who produced comics for Zap were committed to producing their best work for the title. Through 37 years, there wasn't a weak issue in the series, though some would inevitably suffer criticism in comparison to others.

Because of its longevity, Zap Comix also became more than a collection of comic stories, it became a chronicle of a group of brilliant artists, each of them a strong, individual creative voice, as they grew from young men into very old men. A significant degree of my passion for underground comics, and the main reason I began this website, is the stories behind the books; the fascinating histories of all the people who contributed to the patchwork quilt of the underground. Unlike any other underground, Zap Comix conveys the complete history of its creators, from radical experimentation and unbridled passion to seeking personal growth and suffering a death in the family.

Taken in its entirety, Zap Comix is one of the most important comic-book series in the entire history of comic books. There have been many more beautifully illustrated and others had a greater impact on mainstream comic-book characters that were far more important to most comic-book fans, but none were more essential to emancipating and elevating the scope of sequential art for the benefit of a discerning reader. Or as Zap #1 put it, "For Adult Intellectuals Only!" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zap Comix #8 |

Zap Comix #9 |

Zap Comix #10 |

Zap Comix #11 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 9 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zap Comix #12 |

Zap Comix #13 |

Zap Comix #14 |

Zap Comix #15 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 10 |

REVIEW SCORE: 9 |

|

|